Studio Report: Neumann NDH30 Headphones

When is a review not a review? When it started as a report based on six months of real-world use of an audio product but grew into a side-by-side comparison of two complementary audio products. If you’re an audio professional you’ll probably benefit from one, the other, or both…

In April 2021 AudioTechnology published my field report for Neumann’s first headphones, the closed-back NDH20s. It followed many months of using them in the field as my primary headphones for recording music and sounds in remote places – which I reasoned was relevant to the use scenarios they were designed for. Similarly, this report follows months of using Neumann’s second headphones, the NDH30s, in the use scenarios they were designed for: mixing and mastering. Before digging into use scenarios and the NDH30s, however, I must set the context for this report by returning to Neumann’s first venture into the headphone market: the NDH20s. This context is important, so let’s go back to the start…

CTRL + RETURN

After months of using the NDH20s in extreme versions of the use scenarios they were designed for, and considering that they’d been on the market for two years by that time, I couldn’t understand why they hadn’t gained more traction in their target market: audio practitioners who needed headphones that offered reliable sound quality, high isolation, physical ruggedness and portability. Despite having the words ‘Studio Headphone’ clearly displayed on both ear cups, the number of reviews from inside the Studio Headphone market was greatly outnumbered by the number of reviews from outside the Studio Headphone market – predominantly audiophiles, commuters and tech vloggers whose opinions swayed the general consensus inappropriately.

You can’t blame an audiophile, commuter or tech vlogger for unboxing and reviewing a premium-priced product that looks like a prop from ‘The Day The Earth Stood Still’ (the 1951 version with Michael Rennie, of course) and is the first pair of headphones from one of the world’s most revered microphone manufacturers that also happens to be owned by one of the world’s most revered headphone manufacturers. However, from an audio practitioner’s point of view those reviews were largely irrelevant because they were from people who were not part of the audio production workflow. They weren’t relying on their headphones for making last-minute mix revisions in a traffic-jammed Uber en-route to the mastering session, or mixing a live-streamed concert from in the wings. They weren’t swinging a boom arm and wondering how much of the on-set noise was leaking through the headphones and how much was in the captured sound and would be passed downstream. They weren’t studio managers looking for premium headphones that could withstand repeated falls onto a parquetry floor. They weren’t home studio owners chasing reliable translation without resorting to expensive monitor speakers and the proportionally expensive acoustic treatment required to make the most of them. These were all use scenarios that the NDH20s were designed for but were largely overlooked because the majority of reviewers were simply in search of an enjoyable listening experience, not a professional audio workflow experience. They were the people buying the sound, not making it, and were so far downstream of the professional audio workflow that they might as well be at sea – which is where their highly polarised ‘love them or hate them’ reviews left the NDH20s.

What’s all of this got to do with the NDH30s? More than meets the eye, or ear. Let’s summarise it in two parts…

Firstly, because the closed-back NDH20s inspired so many reviews from beyond their target market it’s reasonable to assume that the open-back NDH30s will do the same – they certainly look like an audiophile follow-up to the more industrial NDH20s. So if you’re obsessively absorbing every review you can find about the NDH30s, pay close to attention to the reviewer’s headphone requirements. If you’re an audio pro and the reviewer’s most critical audio decision is whether to use a conical or elliptical stylus, move on…

Secondly, the NDH30s clarify the NDH20s’ position in the audio workflow while simultaneously providing the missing component in a comprehensive monitoring ecosystem that few, if any, manufacturers offer: a collection of midfield monitors, nearfield monitors, closed-back headphones and open-back headphones that are all voiced to work together, and where each provides a meaningful cross-reference for the others. We’ll come back to that comprehensive monitoring ecosystem later. For now, let’s look at the use scenarios that Neumann has designed the NDH series headphones for.

USE SCENARIOS

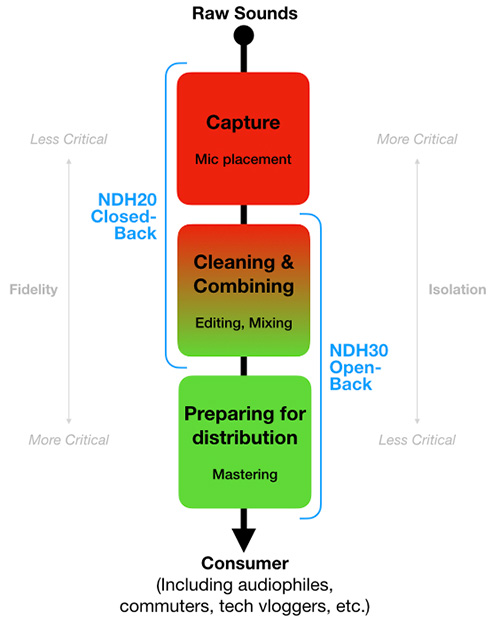

The typical professional audio workflow for music production is shown below. There are differences in terminology for other audio-related industries (sound reinforcement, film, television, radio, social media, etc.), but the basic workflow remains the same: the raw sounds must first be captured (mic choice and placement), then cleaned up and combined (editing and/or mixing), and the combined sound must then be prepared for distribution to the consumer (mastering/processing, etc.).

…from an audio practitioner’s point of view those reviews were largely irrelevant…

According to Neumann’s website the primary features of the closed-back NDH20s are ‘a linear sound balance, like Neumann’s acclaimed studio monitors’, ‘excellent isolation’ and ‘transparent sound’. These features put them where closed-back headphones should be in the audio production workflow: an emphasis on isolation and fidelity so that upstream audio practitioners can ensure the captured sounds are good enough to pass downstream, while also offering enough accuracy for mixing and sub-mixing situations if necessary.

In comparison, Neumann’s website says the primary features of the open-back NDH30s are ‘a linear sound similar to a perfectly calibrated Neumann loudspeaker system’, a ‘high resolution stereo panorama with precise localisation’, and ‘a transparent, detailed sound image ideal for mixing and mastering’. These features put them where open-back headphones should be in the audio production workflow: an emphasis on fidelity and imaging to ensure the results are good enough to pass further downstream to other audio practitioners or directly to the consumer.

Why am I stating the obvious? Because it’s important to note that Neumann has made very clear distinctions between the use scenarios of the closed-back NDH20s and the open-back NDH30s, and those distinctions remain consistent from the design and construction through to the marketing. However, in the areas where both headphones overlap we see that the components are identical and/or interchangeable, and the tonality is correlated and/or transitional. This suggests that the NDH20s and NDH30s are not just two different types of headphones, they’re a complementary pair where each one’s form follows its own function while overlapping the function of the other – as shown in the illustration above. Together they cover the entire professional audio workflow with sufficient tonal overlap in the editing/mixing use scenarios to allow a smooth transition between them.

I am certain that the world doesn’t need another NDH30 review that assesses them as a stand-alone product. You don’t want to read it, and I don’t want to write it. I’m also certain that, despite having the words ‘Studio Headphone’ clearly displayed on both ear cups just as the NDH20s do, many of those reviews are from outside the Studio Headphone market and will therefore be irrelevant and misguiding to working audio professionals. With those two points in mind this report takes a more contextual approach, looking at who and what the NDH30s are intended for, where they fit into the audio production workflow, where they overlap with the NDH20s, where they differ, and how they fit into Neumann’s evolving monitoring ecosystem.

With all of that background out of the way, let’s dig into the open-back NDH30s with the understanding that comparisons with the closed-back NDH20s are not only inevitable but also meaningful and necessary…

STURDY 30

The NDH30s are sold in the same packaging as the NDH20s: a clamshell cardboard box with a ‘monochrome + orange’ colour scheme, adorned with a close-up image of an ear cup on the front and useful data on the back including technical specs and intended use scenarios. It’s good enough to ship them from the manufacturer to you via numerous forms of transport and handling and storage, so it’s probably good enough for your purposes. Give it a layer of gaffer tape and it should last a lifetime.

Tucked behind a flap in the lid is the expected Quick Start visual guide that unfolds to an A4 page, and a multi-language information sheet that unfolds to an A2 page – although unless you’re multi-lingual only about 5% of that page’s total area will be in a language you can read, and if you are multi-lingual then you’ll be re-reading that same 5% of information in different languages. (PDFs instead of paper, please; anyone who can legitimately afford the NDH30s will have 24/7 internet access.) There’s also a neatly-folded black drawstring carrying bag just like the one supplied with the NHD20s, and it retains the same magical quality of expanding upon first unfolding to ensure it never fits back into the plastic bag you just pulled it out of. It’s a good bag for keeping the headphones and cables together, so use it. If you’re not going to use it, don’t take it out of the plastic bag…

At first glance the NDH30s look similar to the NDH20s with the exception of a grille that indicates their open-back design and visually distinguishes them from the NDH20s. It’s made from a thin sheet of steel, perforated in a honeycomb pattern and coated with a layer of black plastic paint that probably provides some helpful damping. It rises to a small dome in the middle, presumably for reinforcement. Denting it seems unlikely without considerable determination.

The NDH30s’ ear pads use a softer, lighter and less dense material than the memory foam used in the NDH20s, and are about 1cm larger in diameter. They’re more forgiving of the arms/stems of glasses, and are clearly built with an emphasis on comfort rather than isolation.

As with the NDH20s, the cable connects via the right ear cup and there’s an embossed L and R on the headband immediately above each respective ear cup. The L is also embossed in Braille (three vertical dots, aka ‘123’) – a nice touch for the visually-impaired, which includes everyone who has to work in the dark spaces behind-the-scenes. Inside the ear cups is the same orange lining seen in the NDH20s.

In the hands the NDH30s feel as rugged and sturdy as the NDH20s. At 352 grams excluding cable they’re 38 grams lighter than the NDH20s, a minor weight difference when the weight of the cable is factored in. They appear to use the same headband, fittings and aluminium-reinforced plastic parts as the NDH20s, while the ear cups are almost certainly derived from the NDH20s’ CAD files. Although both have the same rated ear cup contact pressure of 5.5N to 6.8N, the NDH30s feel gentler on the head – which is probably due to their larger and softer ear pads spreading that pressure over a larger area around the ears while also leaving more room around the pinnae. Perhaps the slightly lower weight helps here as well, or maybe it’s entirely due to how their open-back design maintains an acoustic connection with the surrounding space. Whatever the case, I’m far less aware of wearing the NDH30s than I am of wearing the NDH20s. They’re very comfortable; I can wear them for hours without giving a sigh of relief after removing them.

When the NDH30s and NDH20s are viewed side-by-side, in or out of their boxes, the overall impression is of a matching pair of tools intended to be used as required – rather like switching between Standard or Phillips screwdrivers from the same set. As smartly complementary as they look, they’re both relatively large and heavy compared to popular headphones such as AudioTechnica’s M50X (closed-back) or BeyerDynamic’s DT990 Pro (open-back). You won’t be throwing a pair of NDH headphones into your bag as a fashion statement or a just-in-case afterthought – they’re designed to be used with intent.

In the hands the NDH30s feel as rugged and sturdy as the NDH20s.

DIAPHRAGMETRICS

Both headphones use a 38mm diaphragm with neodymium magnet. Their voicing suggests that both drivers share many things in common (possibly diaphragm material, suspension method, voice coil wire, etc.), although there’ll be differences at the design level because open-back ear cups present fundamentally different acoustic and electrical parameters for the driver designer to deal with. If the driver designer is aiming for a consistent family voicing between open-back and closed-back headphones, these differences have to be accounted for and the appropriate parameters tweaked accordingly. The NDH30s have a slightly lower impedance than the NDH20s (120 ohms versus 150 ohms) which would make them easier to drive to a given SPL except they also have a significantly lower sensitivity (104dB SPL versus 114dB SPL @ 1kHz) which should make them harder to drive to a given SPL. In practice the perceived level difference between them is quite subtle, but that also depends on how the frequency spectrum of the content aligns with the headphones’ differing frequency responses – sometimes you can switch between them without feeling a need to make any level adjustments, other times you’ll want to. [Headphones and frequency response will be discussed further in my forthcoming article ‘About Headphones’.]

The NDH30s have a wider bandwidth, being 3dB down at 12Hz and 34kHz respectively while the NDH20s are 3dB down at 5Hz and 30kHz. Both extend well above and below the frequency limits of human hearing and it could be argued that the differences between their bandwidths are irrelevant, or at least less relevant than the hard-to-avoid differences between open-back and closed-back designs.

Both have the same maximum input power handling of 1000mW and the same continuous input power handling of 200mW. One interesting difference between the NDH20s and NDH30s is the THD specification. At <0.03% THD (1kHz @ 100dB SPL) the NDH30s outperform the NDH20s rating of <0.1% significantly and noticeably. More about that later…

CABLING

The NDH30s are supplied with a single cable that is 3m long, straight, has a fabric outer sleeve (giving it a deluxe feel), and is a pleasure to wear – quite a contrast to the NDH20s’ rugged but touch-sensitive cables. It’s about the same diameter and weight as the straight cable provided with the NDH20s, but its fabric outer sleeve makes it no more touch-sensitive than any other decent headphone cable. I doubt it would survive as many RCROs as the NDH20s’ ruggedised cables [see ‘Cable Trade-Offs’], but RCROs are not indicated in the NDH30s’ use scenarios so therefore it doesn’t matter.

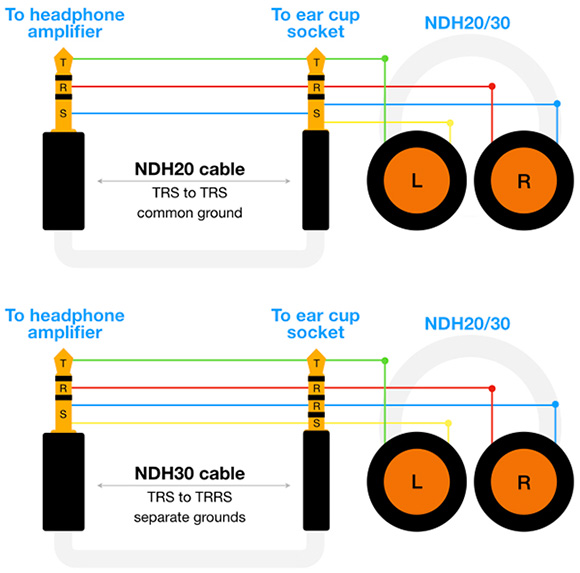

The end that connects to the headphone amplifier is fitted with the typical 3.5mm three-conductor TRS (Tip Ring Sleeve) jack with screw-on 6.35mm adaptor, but, unlike the cables provided with the NDH20s, the end that connects to the headphones uses a four-conductor 2.5mm TRRS (Tip Ring Ring Sleeve) connector. What’s going on here? That extra ring is not to support a headset mic…

The typical headphone cable contains three inner conductors: one for the left channel signal, one for the right channel signal, and one for the ground (which provides the reference for the left and right channel signals). All three conductors run alongside each other for the length of the cable, making it possible for some of each channels’ signal to be induced into the ground conductor. Because the ground conductor is common to both channels, a small amount of each channel’s signal (i.e. that which is induced into the ground conductor) ultimately becomes part of the other channel’s signal – thereby creating inter-channel crosstalk and reducing the stereo imaging. To minimise this problem the NDH30s’ cable uses two separate ground conductors (one for each channel) running throughout the length of the cable, oriented to minimise crosstalk from either channel’s signal conductor into the other channel’s ground conductor. All of this would be a waste of time if the two ground conductors in the cable were summed back into one conductor when they entered the headphones, of course, so the NDH30s maintain the separate ground wires throughout the headphones as well, all the way to the drivers. Hence the use of a TRRS socket.

Neumann refer to this four-conductor cable as being ‘internally balanced’ and describe the NDH30s’ internal wiring scheme as ‘symmetric’ (which also allows them to be driven by a balanced or differential source if given the right cable). Such terms might sound like pandering to the audiophile snake oil industry but the approach is legitimate, and variations on this theme are also used by reputable audiophile headphone manufacturers. Neumann’s Sebastian Schmitz assures me that the combined benefits of the internally-balanced cable and symmetrical wiring are measurable and audible, and I have no reason to doubt him because a) Neumann don’t do snake oil, and b) the NDH30s do have remarkable stereo imaging.

As it turns out, Neumann had the foresight to use symmetric wiring and the TRRS socket inside the closed-back NDH20s as well – even though the cables supplied with the NDH20s are not ‘internally balanced’. This makes the NDH30s’ cable backward-compatible, bringing its improved imaging benefits to the NDH20s while also overcoming the niggles expressed in ‘Cable Trade-Offs’ when using the NDH20s in situations where pinpoint imaging is more important than cable durability. The NDH30 cable is available separately, and might be a good upgrade for your NDH20s…

ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE

I’m always wary of headphone reviews that are based entirely on how they reproduce music that’s already been released, and therefore sidesteps testing them in all of the use scenarios encountered by audio practitioners. It’s all about relevance, and relevance is defined in the use scenarios. The NDH30s’ use scenarios are mixing and mastering, so using a released recording to assess their performance is relevant from a headphone comparison point of view, but it can’t be the only metric because it doesn’t involve actually using them for mixing or mastering. With that in mind I used the NDH30s to re-mix some of my own multitrack sessions, re-master some of my direct-to-stereo recordings of live chamber music performances, and also to undertake some serious work on a selection of live performance desk mixes for a client’s promo video. In situations where the NDH30s’ use scenario overlapped the NDH20s’ use scenario (primarily editing and mixing), I often cross-referenced between the NDH30s and NDH20s to expose and explore differences between them.

Throughout this process I was using CEntrance’s USB bus-powered DACport HD headphone amplifier connected to my Macbook Pro or iPad Pro, using numerous DAW apps and audiophile music player apps in accordance with the NDH30s’ use scenarios of mixing and mastering. For some assessments I went back to putting the raw wav files on SD cards and used the headphone amplifier built into my Nagra Seven field recorder, emulating a ‘capture’ use scenario in which isolation wasn’t required (e.g. in a dedicated recording room inside a concert hall). Between the DACport HD and the Nagra Seven I’d covered the typical circuit topologies the NDH30s would be driven by without resorting to a dedicated mains-powered headphone amplifier – which could possibly deliver better results but at the expense of portability. I didn’t bother testing the NDH30s with the headphone sockets built into my 2013 Macbook Pro and my 2017 iPad Pro due to earlier experiences with the NDH20s: on some material the Macbook Pro’s internal headphone amp struggled with the low frequencies while the iPad Pro’s internal headphone amp was unnecessarily bright. Since switching to CEntrance’s DACport HD I don’t have to deal with those sorts of problems and uncertainties, and I’d assume similar performance would be available from any of the pocket-sized USB bus-powered headphone amps from Audioquest, Chord et al, and perhaps even the headphone amplifiers built into USB bus-powered interfaces. If you don’t need the portability and don’t need an interface, check out the headphone amps from Schiit Audio…

LISTENING EVALUATIONS

For the ‘listening only’ part of this report I used a number of my favourite reference recordings – some well-produced and engineered albums, some borderline albums that highlight a monitoring system’s ability to reveal mix issues and other problems, some that I knew very well because I was part of the audio production workflow, and others for which I was the entire audio production workflow. When making assessments with these reference albums I like to close my eyes and pretend I’m sitting at the controls during the final playback, listening for any last-minute changes I’d want to make: an EQ tweak here, a compressor tweak there, a tad more reverb, whatever. This approach shifts my listening focus towards what the headphones reveal in practice, which is far more relevant than whether or not they provide an enjoyable listening experience. It’s also a lot of fun.

Kind Of Bloud

Starting the day with fresh ears, the first reference was the classic ‘Kind of Blue’ by km Davis (I live in a metric country). Although primarily intended as a ‘feel good’ warm up listen, it is rich in performance noises that remind us of the importance of serving the music first and foremost – anyone who has ruined a sax sound by obsessively EQing out mouth/lip noise will understand this. It also revealed something very important about the NDH30s. Fifteen minutes into the album, approaching the toe-tapping end of ‘Freddie Freeloader’, one of the members of the co-working space sided up to me and whispered something inaudible. Removing the headphones so I could hear properly, she whispered, “What are you listening to?” “Kind of Blue, by Kilometres Davis.” “Kind of Blue? Well, it’s Kind of Loud…” Realising how loud it was coming from the headphones in my hand, I replied with appropriate surprise, “Oh, it is Kind of Loud!” Stifled giggles throughout the co-working space implied that others had long been enjoying (or politely tolerating) the horns of Davis, Coltrane and Adderley leaking through the NDH30s’ open-back ear cups.

What does this experience tell us? Monitoring at unintentionally high SPLs is a common occurrence the first time you use monitors that have significantly lower distortion than you’re used to. For any given monitoring system, over time the ear/brain system learns to associate a certain level of distortion with a certain perceived loudness. When you first change to a monitoring system with significantly lower distortion there’s a subconscious tendency to turn it up until it reaches the distortion level you’re familiar with because that’s when it feels like it is at the level you’re used to. If your new monitoring system has 6dB less distortion than your old monitoring system, on your first listen you could be inadvertently turning the SPL up to 6dB higher than you would normally use because that’s when it feels like it’s at the right level. It won’t be until you try to talk to someone next to you while music is playing that you’ll catch yourself saying “Oh, it’s kind of loud!” I’ve experienced this phenomenon many times, and in every case it has been an indicator of significantly lower distortion from unfamiliar monitors.

At <0.03% the NDH30s’ THD is significantly lower than the NDH20s’ THD, which is already very low at <0.1%. That’s certainly enough of a difference to explain the significant increase of playback level on my first listening of a known reference in a subconscious attempt to reach an SPL that intuitively felt right after spending so long listening with the NDH20s. This ‘low distortion, high SPL’ experience also confirmed the DACport HD’s ability to drive the NDH30s to high SPLs without any audible signs of distress, thereby confirming the NDH30s’ portability.

Realising that I had probably raised my hearing threshold significantly and left my ears in no shape for critical listening, I put the NDH30s away for the day. With refreshed ears I started the next morning by methodically acclimatising my ears to the closed-back NDH20s, imprinting their familiar sound into my perception and getting my monitoring levels right. Then I switched to the NDH30s, made a few careful back-and-forth tweaks to match the SPL, and got on with it. Note that I was monitoring at what I felt was somewhere around 83dB SPL, just like a calibrated studio monitor system would use and as explained in my NDH20 field report. That’s the kind of SPL the NDH series are voiced for, and it’s where you should be using them if you want to get the best out of them.

I listened to many reference recordings through this process and took copious notes, mostly of appeal to audiophiles rather than audio practitioners. Instead of boring you to death with such flourished meanderings, you’ll find a hastily edited version of them tacked on the end of this report – it was never intended to be part of this review but it didn’t take long to tidy up, and we’re not in print so the page count is not an issue. (Yo publishers, see what I did there?) Maybe you’ll find some value in it. Scroll down to ‘Copious Notes’.

WORKFLOW EVALUATIONS

The take-away of the listening tests mentioned above was that the NDH30s deserved serious consideration, so I put them to work on a handful of mixing and mastering tasks. I also fired up my Grover Notting CR1 desktop cross-reference monitors to double-check the spatial, balance and translation decisions that can be difficult to get right when working solely on headphones. Two of these tasks were particularly revealing, one for mixing and the other for mastering. They’re both discussed below.

Mixing: Samples & Bansuri

This multitrack session file consists of a layered backing track made from samples with an improvised bansuri (bamboo flute) part recorded over it. I’ve used it in numerous classrooms, studios and auditoria for over a decade to demonstrate a common problem that occurs when composers use the highly produced/polished sounds from sample libraries to create a backing track to support their solo acoustic instrument performances. Without the skills to give their solo instrument recording the same level of production/polishing heard in the sampled sounds the result is invariably a karaoke mix, i.e. a solo track that is spectrally, spatially and dynamically out of perspective with the backing track it has been plastered over.

The mix that the session opens with is the culmination of many iterations of this demonstration, mixing and tweaking for the best translation through numerous playback and monitoring systems. As such, I wasn’t expecting any surprises when hearing it through the NDH30s and there weren’t any. However, openings were revealed for some worthwhile refinements.

The backing track is built around a kick drum accompanied by a sustained bass drone, adorned with other percussive instruments and pads. Over numerous mix iterations through different monitors in different acoustic environments over many years, the lowest octaves of the kick drum and the bass drone had settled at very conservative levels to avoid becoming boomy when demonstrated through poor speaker systems and/or in acoustically untreated spaces. The conservative level of the low frequencies and the bandwidth they exist within (unoccupied by any other instruments) creates a slightly bass-shy mix that’s easily corrected when you have access to accurate low frequency monitoring, and that’s exactly what happened with the NDH30s. Having experienced how accurately they reproduce low frequencies and reveal their related harmonics during the earlier listening evaluations, I had no qualms in trusting what the NDH30s were telling me when EQing the kick drum and the bass drone individually while simultaneously locking in their harmonic relationship to enhance the overall musicality. I even removed the subtle ducking I had been using for years on the bass drone (triggered by the kick), finding I was getting a much better result with carefully-sculpted EQ.

With the low frequency spectrum sorted, I then found myself making tiny adjustments throughout the mix to fine-tune things further. By this stage the mix sounded good through the NDH30s and the NDH20s. I was able to give it even more ‘resilience’ (i.e. improved translation through a broad range of playback systems) after a few cross-reference listens switching between the NDH headphones and the Grover Notting CR1s, tweaking any sounds that were struggling to be clearly represented on smaller speaker systems while also making sure the levels of spatial effects (reverb, etc.) remained acceptable through headphones and speakers. This was a very satisfying result that also reinforced what I’ve been practising and preaching for years: with a good pair of headphones, a good pair of small cross-reference monitors, the right metering and a bit of experience you can get by without bigger monitors and the associated acoustic treatment required to make the most of them.

…I had no qualms in trusting what the NDH30s were telling me…

Mastering: Piano & Violin Duo

This was a two-mic direct-to-stereo recording of violinist Benjamin Beilman and pianist Andrew Tyson performing in concert at City Recital Hall, Sydney (October 10, 2016), captured with a spaced pair of Sennheiser MKH8020 omnis into my Nagra Seven field recorder. The piano/violin duo is always difficult to capture well when using only a stereo pair above the audience; it pits one of the smallest orchestral instruments against one of the largest. The edited and mastered recording was well received when it went to air all those years ago, but when I recently found it on YouTube I felt that the violin was sometimes dominated by the piano. Ever since then I’ve wanted to re-visit this recording, and preparing this report gave me the appropriate motivation. Loading the original wav files into my Nagra Seven and listening back through its built-in headphone amplifier, the NDH30s showed that the raw recording did not sound as good as I’d hoped to hear. The tonalities of the individual instruments were acceptable but the violin was just managing to hold its own against the piano, and this was mostly due to the duo’s well-balanced playing skills rather than my mic placement skills.

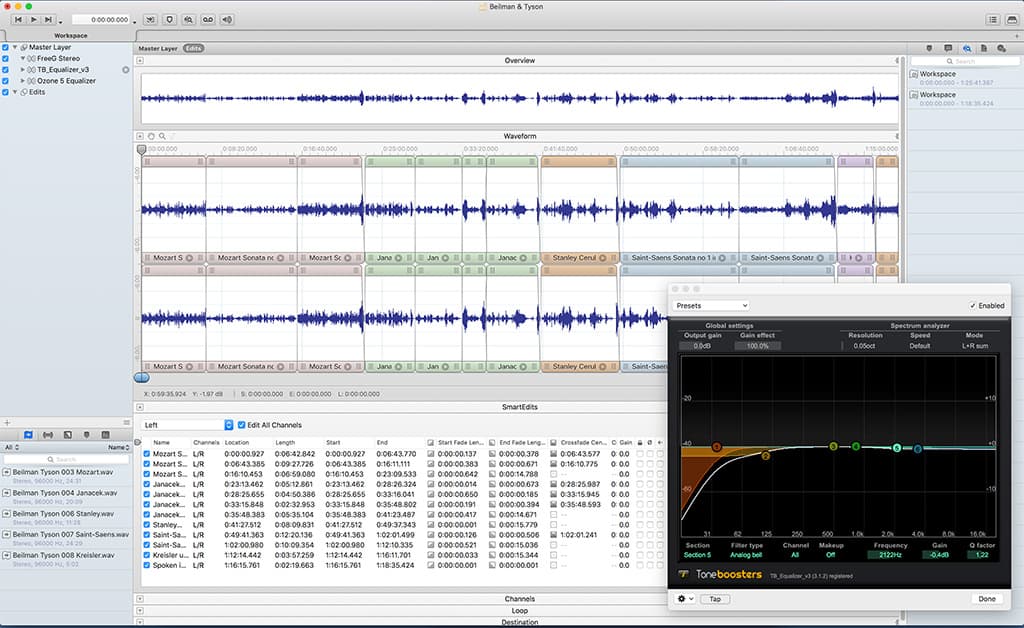

Opening the original DAW session showed that I’d created an increase in the violin’s perceived level with some global EQ, enough to keep it present but not as present as I was hoping to hear, and this was probably helped along by the broadcaster’s on-air processing – so it sounded acceptable on-air but not on YouTube. Being well-acquainted with the NDH30s by this time, I bypassed the previous processing and tackled the job again.

There is no mixing stage for a two-mic direct-to-stereo recording such as this; there’s one mic for the left channel signal, one mic for the right channel signal, and that’s it. The audio production workflow is reduced to capture, edit and master. After double-checking my edits on the NDH20s – taking advantage of their isolation for checking the crossfades and following the fade-outs down to a deeper level of silence than I could reach with the NDH30s or CR1s – this was now essentially a stereo mix ready for mastering.

Photos from the concert set-up showed that the MKH8020s were spaced about 50cm apart (i.e. AB50 technique) and about 4m from the centre of the piano’s keyboard. At this spacing and distance each mic captures essentially the same levels of violin and piano, and the stereo image is created by the arrival time differences between when each instrument’s sound reaches each mic. It was a narrow image in terms of articulation, with the violin’s bowing sounds marginally to the left of centre and the piano’s hammer sounds marginally to the right. The piano’s low frequencies dominated the levels of both tracks but were localised to the right side, of course, creating the lopsided image weighting one often gets when recording piano/violin duos in this two-mic direct-to-stereo manner. I knew I had some room to move if I could introduce some amplitude differences between the two channels.

…the NDH30s showed that the raw recording did not sound as good as I’d hoped to hear

A high pass filter (35Hz, 0.7 Q) cleaned up the subsonic noises of the room and audience, while also saving most speaker systems from struggling to reproduce frequencies that are below their range – which can adversely affect how well they reproduce frequencies within their range. The lowest note on the grand piano, A0, has a fundamental frequency of 27.5Hz at which point the HPF was about 6dB down. This was a compromise I was willing to accept considering a) the total musical value that A0 might contribute to 75 minutes of music from five different compositions spanning over 200 years, b) the HPF would really only affect A0’s fundamental frequency, which was so low that most speakers/rooms would struggle to reproduce it accurately anyway, and c) the 2nd harmonic of A0 (2 x 27.5 = 55Hz) and all harmonics above it would remain mostly unaffected and thereby represent the note sufficiently through most speaker systems. Switching the HPF on and off while monitoring through the NDH30s, with their extended LF response, showed an obvious improvement in cleanliness and clarity with no apparent impact on the music itself. In a more serious situation I would use a spectral view of the entire session to identify the lowest frequency of musical interest and work from there, but the approach described above was sufficient for this ‘after the fact’ purpose.

With the habitual sonic housekeeping out of the way, it was time to introduce some level differences to address the balance and imaging issues. Pulling the right channel’s level down by 2dB moved the overall image slightly to the left, which created a more pleasing image to begin with, and seemed to create a bit more separation between the two instruments – at least when heard in the NDH30s. This was a good start…

The mics used for this recording (Sennheiser MKH8020s) are known for their rich and solid low frequency response, which adds a healthy weight to the sound of a grand piano. Although this is generally considered ‘a good thing’, in this case it made the piano too big in comparison to the violin. A subtle low frequency shelving cut (approx. -2dB, 107Hz, 0.68 Q) applied at differing levels on each channel (bigger cut on the left, smaller cut on the right) made the piano slightly smaller without affecting the lower end of the violin’s range, thereby making the violin relatively bigger. Similarly, a subtle high frequency shelving cut (approx -0.6dB, 3385Hz, 0.5 Q) applied at differing levels to both channels mellowed the piano’s attack without affecting the violin’s upper harmonics to the same extent, essentially moving the violin forward of the piano in the image. Finally, a small dip in the upper midrange (-0.4dB, 2122Hz, 1.22 Q) across both channels tamed some edginess in the violin bowing and some glassiness in the piano that had become more obvious after the low frequency cuts described above. Collectively, the high frequency shelving cuts and the upper midrange dip described above had the added benefit of thickening the pizzis and bringing out a sense of ‘wood’ in the violin’s tone while also sweetening its higher notes – as heard in Janacek’s ‘Violin Sonata’ and Saint-Saens’ ‘Sonata no 1 in D minor op 75’.

With those changes in place the two instruments were now considerably closer to the much-desired ‘even balance’ point where either musician can play assertively to step forward in the mix without being too loud, or play reservedly to move back into accompaniment without being too soft. Cross-checking on the NDH20s and Grover Notting CR1s confirmed that all was good with the level and tonal balance determined with the NDH30s. It now sounded consistently acceptable when auditioned through the NDH30s, the NDH20s, and the CR1s. If this recording was destined for release I would’ve spent more time refining it as described above, but for the purposes of this report I’d heard enough. With the NDH30s I was able to identify relatively small tonal issues between channels on a two-mic direct-to-stereo recording, even at very low frequencies, and confidently correct or utilise them to my favour.

As an interesting footnote to the above: I enjoyed listening to the newly mastered version of this recording more through the NDH20s than I did through the NDH30s. I believe this was primarily due to the NDH20s’ greater isolation and correspondingly greater sonic ‘chiaroscuro’: their isolation providing a sonically blacker background that, in turn, made the upper midrange and subtle highs sound clearer and cleaner. The NDH20s’ isolation also helped reveal the barely audible (pp) violin mutterings that followed a recurring phrase in the 4th movement of the Janacek, which were sometimes hard to hear in the NDH30s due to their open-back design and the soft hum of the air-conditioning in my listening space.

Between the low self-noise of the MKH8020s (10dBA), the respectfully quiet audience and the processing described above (particularly the sculpting of the low frequencies), this recording achieved a very ‘black’ background that was more readily appreciated in the NDH20s than it was in the NDH30s. However, I doubt I would’ve got it to that point using the NDH20s alone because the tonal screwdriver work described above falls outside of their use scenario. It is exactly what the NDH30s are designed for, however, and they made it fast and easy to achieve.

SUMMARISED IMPRESSIONS

If you’ve read this far you’ll know that I performed numerous listening tests with the NDH30s using finished recordings that had already been through the entire audio production workflow, from capture to distribution. You’ll also know that I put the NDH30s to work in numerous real-world applications within their use scenarios, two of which were detailed above.

The following provides an overall summary of the NDH30s’ sonic performance based on the listening tests and the real-world applications, and often using the NDH20s as a point of comparison.

Spectral Balance

The most obvious thing to note is that the NDH30s have slightly more energy in the upper mids and highs than the NDH20s. The NDH20s initially seemed a bit heftier in the bottom end, but that impression proved to be due to their comparatively subdued midrange and highs – they didn’t have more bottom end, they were just marginally darker. [See ‘Subby Kicks’ in the Copious Notes below…]

In my field report for the closed-back NDH20s I commented that they sounded less like headphones and more like a calibrated monitoring speaker system, describing their slightly subdued upper mids and highs as follows: “They seem to have been ‘voiced’ to put a metre or two of air between you and the drivers, just like studio monitors – except they’re up against your ears, leaving nowhere for small details to hide.” Interestingly, for the open-back NDH30s Neumann’s website specifically states that they have ‘a linear sound, similar to a perfectly calibrated Neumann loudspeaker system’, and later refers to similarities with a speaker monitoring system that has been calibrated via Neumann’s MA1 Monitor Alignment system. The designers at Neumann have pulled off this ‘making headphones that sound like calibrated studio monitors’ trick in a far less obvious manner than they did (or could?) with the closed-back NDH20s. [Headphones, frequency response and calibration will be discussed further in my forthcoming article ‘About Headphones’.]

Also of note is the NDH30s’ performance in the low and low midrange bandwidths. The low frequency performance is very similar on both NDH headphones, but the NDH30s’ significantly lower THD, more prominent midrange and open-back design collectively allows them to resolve greater detail in the lower midrange than the closed-back NDH20s can, making it easier to identify and work within the harmonics of low frequency instruments. In addition to enabling precise tonal sculpting of kick drums and similar weighty sounds, this also makes it easier to pull off the old bass guitar trick of reducing the fundamental frequencies while boosting the second harmonics (i.e. an octave above the fundamentals). Performed subtly – typically with careful application of two low frequency shelves – this trick automagically makes the bass sound clearer and bigger in the mix while clearing some space in the spectrum for the kick’s fundamental frequency to propel and punctuate the music like it’s supposed to. You already knew how to do that trick, of course, but with the NDH30s you can do it faster and better.

Previously unheard details that were revealed in the closed-back NDH20s with just a bit of careful listening are easier to find and more detailed in the open-back NDH30s provided there isn’t too much external noise coming from your listening environment. If an intentionally backgrounded sound was sufficiently audible in one pair without being too obvious in the other, it was probably at just the right level. This was a recurring observation throughout my NDH30 listening tests, and often lead me back to the NDH20s to see how they presented the same small details. (A good test for this kind of low level resolution is to intentionally turn an instrument’s level down in the mix until it is barely audible through one monitoring system, then check its audibility through the other monitoring system.)

Imaging & Depth

Many moons ago I created some imaging test signals consisting of frequency sweeps and short bursts of pink noise that pass through/across the stereo image. Originally intended to demonstrate the differences between intensity-based stereophony (as used by the pan pot and all coincident microphone pairs) and time-based stereophony (as used in AB microphone pairs), it has also proven to be a great test for the stereo imaging abilities of speakers and headphones. When localising the image via headphones or speakers, the smaller the ‘dot’ of sound is localised in the stereo image, the better the matching of the drivers and the better overall imaging you can expect from them. With the NDH30s the ‘dot’ is very small and well-defined, with none of the shifting or blurring at some frequencies that indicates a mismatch between drivers. It is the most ‘pin-point’ left-to-right imaging I can recall hearing in headphones.

I’ve always found depth much harder to judge on headphones than on speakers. With the NDH30s it’s quite easy to get a feel for relative depth (how much closer one instrument is compared to another) and to a lesser extent absolute depth (how far an instrument is from the listener in a direct-to-stereo recording), but in a recording/mixing situation I’d still want to cross-reference this kind of spatial stuff on speakers. I should also point out that I think both headphones do an excellent job of reproducing depth as far as headphones are concerned, but in different ways. Beyond the qualities that both headphones have in common, the NDH20s’ depth reproduction is helped along by their high isolation and associated blackness, while the NDH30s’ depth reproduction is helped along by their excellent imaging and lower distortion.

DIFFERENT HORSE, SAME SADDLE…

There is a consistent family tonality to be heard in the open-back NDH30s and their closed-back counterpart the NDH20s, but do they sound the same? No, because they’re not supposed to sound the same. Rather, they reflect an understanding that there’s no such thing as a single pair of headphones for all use scenarios. When it comes to passive headphones that you can easily slip on and off and pass around to others, there are two contrasting realities: the highest isolation requires closed-back ear cups, while the highest fidelity requires open-back ear cups. It is better to make a correlating series of headphones in which each pair capitalises on the strengths of its fundamental design, rather than compromising those strengths in an attempt to make them sound the same.

The NDH20s exploit the strengths of closed-back ear cups in accordance with their use scenario, and do a remarkable job of delivering high isolation with high fidelity. The NDH30s exploit the strengths of open-back ear cups in accordance with their use scenario, and their lack of isolation allows them to deliver even higher fidelity. Switching from the NDH20s to the NDH30s mid-workflow – in accordance with their use scenarios – shows that it’s easy to transition from one to the other at the appropriate time without any major disruptions because they are ultimately variations on the same tonality. The NDH30s pick up where the NDH20s leave off in the professional audio workflow, trading isolation for higher fidelity. It’s rather like changing horses midstream but keeping the same saddle so it doesn’t feel too different.

CONCLUSION

Unlike the NDH20s, the NDH30s’ tonality is not something you need to be aware of when working with them. I don’t feel like I have to keep remembering that they’re slightly bright, slightly dull, slightly bass heavy, slightly forward, slightly reserved or slightly whatever. In fact, they sound just about right. They’re one of the few headphones I’ve used that get out of the way and don’t require compensating for any particular characteristic – beyond the considerations that all headphones require when making decisions regarding panning and spatial effects. So where do they fit in the audio production workflow, and are they for you?

The closed-back NDH20s give you the isolation and fidelity required for the initial structural work of capturing, editing and blending sounds. The open-back NDH30s take over from the NDH20s when isolation is no longer needed, providing the higher fidelity required to zoom in for the finer detailed work of sculpting sounds, blending them together and polishing the end result. They’re both voiced to work well alongside Neumann’s KH series of studio monitors, so if you’re experienced with using accurate monitors you shouldn’t have any problems working with either of the NDH series headphones.

If you can only afford one pair of headphones and had to choose between the NDH20s and NDH30s, let that decision be made by whether or not you need isolation. If you mostly work in the capture and live mixing side of the audio workflow (e.g. sound reinforcement, live streaming, etc.) where isolation is vital, you’ll get by very well with a pair of NDH20s and a modicum of restraint in the high frequencies as explained in my earlier NDH20 field report. If you mostly work in the studio mixing and mastering side of the audio workflow, where isolation is not a requirement, you’ll definitely appreciate and benefit from the higher fidelity of the NDH30s.

If you’re a solo operator doing the entire audio workflow from start to finish, or an audio factotum who can jump in and out of the workflow at any point, it makes sense to have both. The NDH20/NDH30 combo covers all use scenarios with two complementary headphones that provide a smooth transition from one to the other, while leaving little doubt about which pair to use and when. Rather than giving you conflicting versions of the same sound and leaving you uncertain as to which version to trust, they provide correlated versions from different perspectives. There’s no need to do the fingers-crossed ‘line of best fit’ mix because it’s unlikely that one pair will tell you something is good if the other pair tells you it’s bad. The NDH20/NDH30 combo may seem like an expensive solution but it’s chicken feed compared to the cost of studio monitors that are capable of equivalent performance, and forms a highly portable reference that is independent of room acoustics.

After using the NDH30s for some time now, individually and alongside the NDH20s, it’s clear that what I suspected in my NDH20 field report is true: Neumann’s foray into the headphone market was not simply an exercise in selling re-badged headphones from Sennheiser (its parent company). The NDH range, as it currently stands at least, is part of an evolving monitoring ecosystem based on understanding the professional audio workflow, assessing the monitoring needs of audio practitioners within that workflow, and designing an intersecting set of monitoring tools to meet those needs.

Many other manufacturers offer excellent closed-back and open-back headphones but I’ve yet to hear a headphone tag-team that works as synergistically as the NDH20/NDH30 combo, let alone one that also correlates with a range of monitor speakers built around the same design philosophy. Very few professional headphone manufacturers also make professional studio monitors, and even fewer can combine Neumann’s deep understanding of the professional audio workflow with the headphone design expertise of a company like Sennheiser and the monitor design expertise of a company like Klein & Hummel (the ‘KH’ in Neumann’s monitor speaker model numbers). No wonder they’ve created such a carefully delineated and correlating range of monitoring products.

If you’re in the market for a pair of open-back headphones, either to round-out an existing monitoring system or as the first step towards a new monitoring system, be sure to audition the NDH30s. If nothing else, they’ll provide an excellent data point that might even convince you to re-assess your budget. On that note, I’m going to close with a small but telling anecdote. At one point during the six months of testing and taking notes for this report I chatted on social media with an aspiring young engineer who was on the hunt for good headphones. After considering his increasingly bleak opinions of the headphones he’d been auditioning within his price range, I recommended auditioning the NDH30s as a point of reference. After doing so he replied: “Oh that’s what headphones are supposed to sound like.” Indeed. In those nine words he’d unknowingly summarised the thousands of words I’ve written above. “My work here is done” I stammered, slipping the NDH30s into their drawstring bag and fading into the shadows…

A very interesting review. I would add that, in my studio setup, it is viable to switch from NDH-20s for their intended function, as you’ve stated, to Neumann’s KH80 DSP speakers for the ‘open back’ mastering stage. In my experience these two work in tandem as well as you describe the NDH-20/30 pairing, except that it is refreshing to have no ‘cans’ on one’s head for one of them!

That makes sense…

With all of their monitors speakers calibrated to the same reference, and all of their headphones calibrated to sound like their monitors (I suspect we’ll see the term ‘the Neumann curve’ popping up in future headphone discussions, just as ‘the Harman curve’ is used now), I think any two items from Neumann’s evolving monitoring ecosystem should work together in a complementary manner whereby each one confirms what the other tells you. One might tell you that a problem is worse or better than the other, but hopefully we won’t have that problem where one monitoring tells us the vocals are too loud and the other tells us they’re too soft! That kind of thing is very confusing and leads to ‘line of best fit’ mixing that relies on mastering to sort it out…

Very interesting and useful review. Thankyou. I use both 20’s and 30’s in my studio (TES Productions), along with Neuman KH 150’s, KH120’s/KH750 and KH 310’s.

I am particularly interested in your comments about the family cohesiveness of the Neumann family. I find this to be certainly true.

I am glad that you found the review interesting and useful, Thomas. As a reader with an extensive Neumann-based monitoring system, it is good to see that you agree with my comments about the family cohesiveness. I felt that this was an important point that is not getting enough coverage in general. Very few other manufacturers are in the position that Neumann is in – making mics, monitor speakers and headphones – with the ability to strive for consistency between them all. And, not long after this review was published they released their audio interface. Apart from being a reputable giant of the industry, they are tapping into the skills of other reputable giants to make a very interesting family of products. I’m keen to see where they go next, if anywhere, with headphones…